Our Mission

At Concordia Academy our mission is:

“To form students in faith, hope, and love, by cultivating wisdom and nourishing their souls in the pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty, according to the Word of God and the Lutheran Confessions.”

“To form students in faith, hope, and love, by cultivating wisdom and nourishing their souls in the pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty, according to the Word of God and the Lutheran Confessions.”

|

Right off the bat we admit that our school isn’t neutral. It’s not passive. It’s not “student led” or “child-centered”—at least, not in a way that leaves the direction of their development up in the air. When we say that our mission is “to form students…” we mean that we’ve got an ideal in mind. We know where we’re going (or at least where we want to go) with them. Admittedly, it’s not as though they’ll come to us un-formed or neutral. They’ll come in all shapes and sizes—and I don’t mean physically, though that, too. They’ll already be formed in part by whatever home-life happens to look like. They’ll be formed by their friends. They’ll be formed by whatever preaching they’ve been given to hear and whatever church-life (or not) they’ve been given to witness and experience. Some will come formed with very hard edges, others overly soft and malleable. Some will come formed with fear and humility, others with an unnecessary boastful pride. However they come, we’ll tell them right up front that we have plans for how they’ll go. In this way, Concordia Academy seeks to be intentionally formative on who they are as humans.

|

“Luther Making Music in the Circle of His Family,” Gustav Spangenberg, 1875

|

The question is: what sort of humans do we seek to form them into? What is this ‘ideal’ towards which we’re directing them? For that we offer the next part of our mission statement: “faith, hope, and love…”. The ideal human that Concordia Academy deliberately seeks to form is one marked by faith, hope, and love. Of course, these three come from St. Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, where he says,

“For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I have been fully known. So now faith, hope, and love abide, these three; but the greatest of these is love.” (1 Cor 13:12-13)

There’s now and there’s the not yet. Now, we don’t quite see things as they are—neither our sin in all of its sinfulness, nor our righteousness in all of its splendor—but then we will. Now, we don’t quite know as we ought to know—either how things work, or the universe operates, or even what we want—but then we will know as He knows us: fully and completely. Concordia Academy recognizes that it exists in the now for people living in the now and yet orders everything it does towards the not yet, where they are ultimately headed. That’s our hope, built on our faith, and expressed by love both now in this life and not yet in the life to come—which is why the greatest of these is love.

But how do you do that? Well, one thing we plan to have at Concordia Academy is a school garden. Gardens beautifully teach patience. You plant one day, spend many days cultivating whatever’s planted—flower, fruit, or vegetable—and then you wait. Cultivating a garden requires watering and tilling and weeding and pruning. It’s taking away what gets in the way and nourishing with what gives life and growth. This formation in faith, hope, and love, we say, will come by “cultivating wisdom and nourishing their souls…”.

To this the Scriptures are clear: “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom” (Prov 9:10; Ps 111:10). “Wisdom,” Proverbs says, was “at the beginning of his work…like a master workman” (Prov 8:22,30). And St. Paul proclaims “Christ…the wisdom of God” (1 Cor 1:24).

The point is this: at Concordia Academy we seek to cultivate wisdom by delivering Christ in all that we say and do, nourishing their souls in the pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty—each of which finds its fullness in Christ Jesus. He is “the Way, the Truth, and the Life” (Jn 14:6). He is “the Good Shepherd” (Jn 10:11). And He is the one we see as we “gaze upon the Beauty of the Lord” (Ps 27:4).

All of this, you see, is done “according to the Word of God and the Lutheran Confessions.” The Scriptures are the basis of all that we teach and all that we do. As St. Paul says, “All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work.” (2 Tim 3:16-17)

This is what we’re about at Concordia Academy. It’s our mission. Will you join us in it?

But how do you do that? Well, one thing we plan to have at Concordia Academy is a school garden. Gardens beautifully teach patience. You plant one day, spend many days cultivating whatever’s planted—flower, fruit, or vegetable—and then you wait. Cultivating a garden requires watering and tilling and weeding and pruning. It’s taking away what gets in the way and nourishing with what gives life and growth. This formation in faith, hope, and love, we say, will come by “cultivating wisdom and nourishing their souls…”.

To this the Scriptures are clear: “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom” (Prov 9:10; Ps 111:10). “Wisdom,” Proverbs says, was “at the beginning of his work…like a master workman” (Prov 8:22,30). And St. Paul proclaims “Christ…the wisdom of God” (1 Cor 1:24).

The point is this: at Concordia Academy we seek to cultivate wisdom by delivering Christ in all that we say and do, nourishing their souls in the pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty—each of which finds its fullness in Christ Jesus. He is “the Way, the Truth, and the Life” (Jn 14:6). He is “the Good Shepherd” (Jn 10:11). And He is the one we see as we “gaze upon the Beauty of the Lord” (Ps 27:4).

All of this, you see, is done “according to the Word of God and the Lutheran Confessions.” The Scriptures are the basis of all that we teach and all that we do. As St. Paul says, “All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work.” (2 Tim 3:16-17)

This is what we’re about at Concordia Academy. It’s our mission. Will you join us in it?

Concordia AcademyA Lutheran Liberal Arts Education

Part of what stands in the way of Classical Lutheran education is a different set of ideas about what education is. Perhaps it’s not a bad idea to ask: What is education? Why do we do it? What is its purpose? These are big, broad, whole picture types of questions. And too often we simply jump into education without ever reflecting on what it is or why we do it.

|

“Education” comes from two different, though very similar, Latin roots: educare and educere. The first means “to form, shape, or mold.” The second means “to draw or lead out.” These two roots wonderfully capture what it is we’re trying to do. However, they don’t yet answer the question, at least not in any concrete way yet. To do that, we need to know what we’re going to form, shape, and mold these children into. We need to know where they’re coming from and where we intend to lead them. When we face those questions, we see that at the core of what it means to educate are the theological presuppositions of creation, fall, redemption, and the eschaton (the end and fulfillment of all things).

What holds all of this together is, of course, the person of Jesus Christ. He says, “I am the Alpha and the Omega, the first and the last, the beginning and the end” (Rev 22:13). So the sort of education you’ll find at Concordia Academy is one centered on Christ, where He is the goal toward which we lead and draw our students and He is the form after which we seek to shape our students.

This Christ-centered education presupposes that man is created in the image of God; that in the fall this image is distorted, destroyed, and requires re-formation; that man is re-formed by God himself, entering into our humanity, joining Himself to us and drawing us into him; and that where we are going—our end, goal, and telos—is union with God in the person of Jesus Christ.

So how do we do that? How do we form, shape, and mold our children, leading them from their fallen image bearing life, into the very life of God in Christ? At Concordia Academy we believe that this is done by cultivating wisdom and virtue—what we might also call faith and love—and by nourishing their souls on what is true, good, and beautiful, by means of the seven liberal arts and the catechetical life of the church.

Why do we speak of the true, the good, and the beautiful? Well, for two reasons: one, because in Himself,

God is true: “I am the way, the TRUTH, and the life” (John 14:6);

He is good: “I am the GOOD shepherd” (John 10:11);

and He is beautiful: “Behold, you are BEAUTIFUL, my beloved, truly delightful” (Song of Solomon 1:16).

And secondly, because His truth, goodness, and beauty have been instilled into His creation. Those who bear the image of God, also bear truth, goodness, and beauty.

Admittedly, with the fall these are all distorted. Nevertheless, the law has been written on our hearts. And because it was by our Lord’s word that all of creation came into being, St. Justin Martyr could say, “whatever is true is ours.”

Perhaps the greatest conflict of ideas over the last 75-100 years, has been whether or not there is such an objectivity to truth, goodness, and beauty. At Concordia Academy we say “yes!” But the progressive education that began with Dewey around the time of World War I, and has only gained momentum through our post-modern culture, issues a resounding “no.”

If we think that truth, goodness, and beauty find their fullness in Christ, then we can take whatever shares in that truth, goodness, and beauty and lead our children from the distortions of sin to their reality in Christ.

This ultimately is our goal. We want to educate our children and are convinced that this means bringing them to Jesus. This happens in the Church through the preaching of the Gospel and the giving out of our Lord’s gifts in the Sacraments. It happens at home as father and mother teach their children to pray and the beautiful stories of salvation in Scripture. And it happens in school, when we take what is true, good, and beautiful in this world—and the stories handed down—and teach our children that all of it reflects Christ for us.

This Christ-centered education presupposes that man is created in the image of God; that in the fall this image is distorted, destroyed, and requires re-formation; that man is re-formed by God himself, entering into our humanity, joining Himself to us and drawing us into him; and that where we are going—our end, goal, and telos—is union with God in the person of Jesus Christ.

So how do we do that? How do we form, shape, and mold our children, leading them from their fallen image bearing life, into the very life of God in Christ? At Concordia Academy we believe that this is done by cultivating wisdom and virtue—what we might also call faith and love—and by nourishing their souls on what is true, good, and beautiful, by means of the seven liberal arts and the catechetical life of the church.

Why do we speak of the true, the good, and the beautiful? Well, for two reasons: one, because in Himself,

God is true: “I am the way, the TRUTH, and the life” (John 14:6);

He is good: “I am the GOOD shepherd” (John 10:11);

and He is beautiful: “Behold, you are BEAUTIFUL, my beloved, truly delightful” (Song of Solomon 1:16).

And secondly, because His truth, goodness, and beauty have been instilled into His creation. Those who bear the image of God, also bear truth, goodness, and beauty.

Admittedly, with the fall these are all distorted. Nevertheless, the law has been written on our hearts. And because it was by our Lord’s word that all of creation came into being, St. Justin Martyr could say, “whatever is true is ours.”

Perhaps the greatest conflict of ideas over the last 75-100 years, has been whether or not there is such an objectivity to truth, goodness, and beauty. At Concordia Academy we say “yes!” But the progressive education that began with Dewey around the time of World War I, and has only gained momentum through our post-modern culture, issues a resounding “no.”

If we think that truth, goodness, and beauty find their fullness in Christ, then we can take whatever shares in that truth, goodness, and beauty and lead our children from the distortions of sin to their reality in Christ.

This ultimately is our goal. We want to educate our children and are convinced that this means bringing them to Jesus. This happens in the Church through the preaching of the Gospel and the giving out of our Lord’s gifts in the Sacraments. It happens at home as father and mother teach their children to pray and the beautiful stories of salvation in Scripture. And it happens in school, when we take what is true, good, and beautiful in this world—and the stories handed down—and teach our children that all of it reflects Christ for us.

What is Lutheran about Classical Lutheran Education?Well, first of all, that assumes there’s something distinctively Lutheran in the first place. Is it sauerkraut, Jello-salads, or casseroles? No, of course not. Is it a particular way of talking or worshiping, singing or celebrating? What does it mean to be Lutheran?

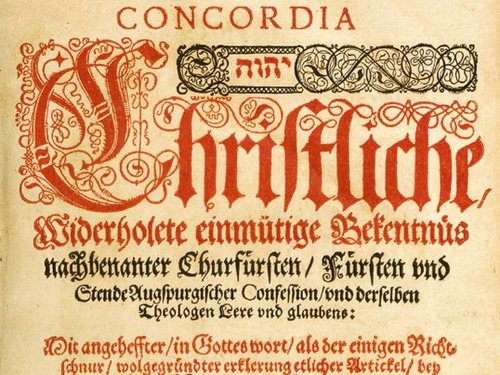

For this we’re best off looking at what makes us Lutheran: our Lutheran Confessions in the Book of Concord. A series of documents were compiled in 1580 including the three ancient Creeds (Apostles’, Nicene, and Athanasian), as well as Luther’s Catechisms, and various Confessions ranging from 1530-1577, all under the title Concordia. |

Concordia comes from two Latin words meaning “with” and “heart.” That is, these confessions are made with unity of heart because they accord with the truth of God’s word. In the preface to Concordia these confessors say:

“In this work of concord, we have not at all wished to create something new or to depart from the truth of the heavenly doctrine, which our ancestors (renowned for their piety) as well as we ourselves, have acknowledged and professed…But, the Spirit of the Lord aiding us, we intend to persevere constantly, with the greatest harmony, in this godly agreement.” (Preface, 23)

To be Lutheran, then—and to uphold the Lutheran confessions, Concordia—is to say nothing new: no new doctrine, no new practice, no new customs or ceremonies. “We have mentioned only those things we thought it was necessary to talk about so that it would be understood that in doctrine and ceremonies we have received nothing contrary to Scripture or the Church universal.” (Augsburg Confession, Conclusion, 5)

“In this work of concord, we have not at all wished to create something new or to depart from the truth of the heavenly doctrine, which our ancestors (renowned for their piety) as well as we ourselves, have acknowledged and professed…But, the Spirit of the Lord aiding us, we intend to persevere constantly, with the greatest harmony, in this godly agreement.” (Preface, 23)

To be Lutheran, then—and to uphold the Lutheran confessions, Concordia—is to say nothing new: no new doctrine, no new practice, no new customs or ceremonies. “We have mentioned only those things we thought it was necessary to talk about so that it would be understood that in doctrine and ceremonies we have received nothing contrary to Scripture or the Church universal.” (Augsburg Confession, Conclusion, 5)

|

This presents a bit of a problem: if the Lutheran Confessions make us Lutheran; and the Lutheran Confessions claim to say and do nothing new; what does it mean to be Lutheran, then?

Again, our Confessions give us our answer, ordering our faith under the word: “We believe, teach, and confess that the only rule and norm according to which all teachings, together with all teachers, should be evaluated and judged (2 Timothy 3:15-17) are the prophetic and apostolic Scriptures of the Old and New Testament alone.” |

(Formula of Concord, Epitome, Summary, 1)

To be Lutheran is to have the Scriptures alone as “judge, rule, and norm;” and to have the writings of the Fathers, the Reformers, and Saints of all times and places as testimonies to and declarations of the faith given in the Scriptures.

Our belief, teaching, and confession at Concordia Academy will follow this lead. The Scriptures are our

“only true standard and norm by which all teachers and doctrines are to be judged” (Formula of Concord, Solid Declaration, Summary, 2). After the Scriptures—and judged by them—are the Creeds and Confessions of the early Church and Concordia. Then come the testimonies of various Councils and theologians, including the Lutheran Confessors and even today’s theologians. What we teach, preach, and confess at Concordia Academy is nothing new. Our students will learn that “the faith once delivered to the saints” (Jude 3) is defended and confessed in all times and all places and finds a great heritage of confessors throughout the history of the Church. We seek to uphold that history and tradition all because it accords with the Word of God. So it goes also for our worship—which we’ll discuss in the next article.

Find out more about these Lutheran Confessions, Concordia, by getting yourself a copy here. You’ll also find loads of helpful information about the Book of Concord, its texts and history, at www.bookofconcord.org.

So what is Lutheran about Classical Lutheran Education? It’s first and foremost being rightly ordered under the Word.

To be Lutheran is to have the Scriptures alone as “judge, rule, and norm;” and to have the writings of the Fathers, the Reformers, and Saints of all times and places as testimonies to and declarations of the faith given in the Scriptures.

Our belief, teaching, and confession at Concordia Academy will follow this lead. The Scriptures are our

“only true standard and norm by which all teachers and doctrines are to be judged” (Formula of Concord, Solid Declaration, Summary, 2). After the Scriptures—and judged by them—are the Creeds and Confessions of the early Church and Concordia. Then come the testimonies of various Councils and theologians, including the Lutheran Confessors and even today’s theologians. What we teach, preach, and confess at Concordia Academy is nothing new. Our students will learn that “the faith once delivered to the saints” (Jude 3) is defended and confessed in all times and all places and finds a great heritage of confessors throughout the history of the Church. We seek to uphold that history and tradition all because it accords with the Word of God. So it goes also for our worship—which we’ll discuss in the next article.

Find out more about these Lutheran Confessions, Concordia, by getting yourself a copy here. You’ll also find loads of helpful information about the Book of Concord, its texts and history, at www.bookofconcord.org.

So what is Lutheran about Classical Lutheran Education? It’s first and foremost being rightly ordered under the Word.

|

“Storyteller” by Anker Grossvater, 1884

|

On Stories

I’m not a good story-teller. But I’d like to be. Stories, well told, are powerful. They have a way of drawing you in. They call to you, perhaps some hidden part of you that you’re normally too busy to notice or pay any attention to. They reach deeper into you than just what you’re thinking. Sometimes after a good story you come away and can’t say exactly what you liked about it, but also don’t feel the need to do so. Stories delight us. They call us to action without saying so. They teach us without giving any assignment. And the best ones call us to be more ourselves than we thought we could be.

Now, to be a good story-teller doesn’t require any academic degree. You don’t need a formal education, so to speak, to tell stories. But you do need an education. That is, you need to be drawn in and led along. So, to tell good stories, you need good stories. You need to hear good stories, read good stories, and pay attention to the world around you—for the Lord is writing your good story as we speak. |

When I say that I’m not a good story-teller it’s because, too often, I get caught up in the rush of things: getting things done, checking off my list, skimming the facts, and knowing just what’s needed. But stories—though built upon facts and things that are done (or left undone)—are more than what you get in cliffs notes or Wikipedia. Stories have color and shape, texture and taste. They sit for just a minute as the setting sun turns from its reddish orange to its pinkish purple. Sometimes life doesn’t let you sit there—but that, too, is a story.

It’s not the pace of life, necessarily, that fights against the story; it’s the inability to reflect or think or even pray while it’s all going on. And that is what a classical education wants to instill—perhaps more than anything else. An ability to reflect on the realities of life—both in its speed and calm—through the thoughtful perception of story.

At Concordia Academy we want to form story-tellers. Some of those story-tellers may go on to be preachers. Some may be barbers. No matter what the vocation to which our Lord calls, everyone likes a good story. To be able to tell these stories, whatever the Lord may have in store, will require a steady diet of good stories. That will be the pride of this school. Whether it’s the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf or Plato’s Dialogues, Wendell Berry’s Jayber Crow or Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings; whether pagan or Christian; the story will teach us to tell our own story. And the better the story going in, the better the story that comes out.

I truly believe that what we need in this world are better stories. As you’ve likely come to know, there are plenty of bad stories. There are stories that lead to darkness, not light; or to evil, rather than the good. In a world increasingly marked by ugly stories, let us fill them with the beautiful. The story that will guide our reception of all stories is the story of all stories: the story of Christ.

Now, don’t get upset about me calling the person and work of Christ “a story.” Yes, there are facts (doctrines) that are vitally important. And yes, there are very good and true morals that must be taught. But when it comes down to it, the way that our Lord desired for us to know Him wasn’t through a set of propositions. It was through a story. It was the story of creation…and the fall. It was the story of Abraham and Isaac and Jacob and Moses…and then Joshua. Ultimately, of course, all of this—real as it was—is a shadow of the true story of Jesus Christ. It’s His story—from the conception by the Holy Spirit in the Virgin Mary to His birth in a manger, His being lost in Jerusalem, His preaching, teaching, calling disciples, casting out demons, dining with Pharisees, weeping with Mary and Martha, overturning tables, suffering, dying, rising, and ascending. And here’s the kicker: He calls us into His story—or, you might say, His story is for us and our story, that we might be for Him and participate in His story. Every other story—from Socrates to Milton to the story of chemical engineering (there’s got to be a story there!)—is a reflection of and an invitation to this story of Christ. “He who descended is the one who also ascended far above all the heavens, that he might fill all things” (Eph 4:10).

We at Concordia Academy will give these stories to our students in order to delight their souls in what’s true and good and beautiful. Thereby we hope to lead them to find their own story as another reflection of Christ and His story. And in so doing, send them with their story as an invitation to others that they too might share in His story.

It’s not the pace of life, necessarily, that fights against the story; it’s the inability to reflect or think or even pray while it’s all going on. And that is what a classical education wants to instill—perhaps more than anything else. An ability to reflect on the realities of life—both in its speed and calm—through the thoughtful perception of story.

At Concordia Academy we want to form story-tellers. Some of those story-tellers may go on to be preachers. Some may be barbers. No matter what the vocation to which our Lord calls, everyone likes a good story. To be able to tell these stories, whatever the Lord may have in store, will require a steady diet of good stories. That will be the pride of this school. Whether it’s the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf or Plato’s Dialogues, Wendell Berry’s Jayber Crow or Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings; whether pagan or Christian; the story will teach us to tell our own story. And the better the story going in, the better the story that comes out.

I truly believe that what we need in this world are better stories. As you’ve likely come to know, there are plenty of bad stories. There are stories that lead to darkness, not light; or to evil, rather than the good. In a world increasingly marked by ugly stories, let us fill them with the beautiful. The story that will guide our reception of all stories is the story of all stories: the story of Christ.

Now, don’t get upset about me calling the person and work of Christ “a story.” Yes, there are facts (doctrines) that are vitally important. And yes, there are very good and true morals that must be taught. But when it comes down to it, the way that our Lord desired for us to know Him wasn’t through a set of propositions. It was through a story. It was the story of creation…and the fall. It was the story of Abraham and Isaac and Jacob and Moses…and then Joshua. Ultimately, of course, all of this—real as it was—is a shadow of the true story of Jesus Christ. It’s His story—from the conception by the Holy Spirit in the Virgin Mary to His birth in a manger, His being lost in Jerusalem, His preaching, teaching, calling disciples, casting out demons, dining with Pharisees, weeping with Mary and Martha, overturning tables, suffering, dying, rising, and ascending. And here’s the kicker: He calls us into His story—or, you might say, His story is for us and our story, that we might be for Him and participate in His story. Every other story—from Socrates to Milton to the story of chemical engineering (there’s got to be a story there!)—is a reflection of and an invitation to this story of Christ. “He who descended is the one who also ascended far above all the heavens, that he might fill all things” (Eph 4:10).

We at Concordia Academy will give these stories to our students in order to delight their souls in what’s true and good and beautiful. Thereby we hope to lead them to find their own story as another reflection of Christ and His story. And in so doing, send them with their story as an invitation to others that they too might share in His story.